BRILLIANT DAM

West Kootenay Power & Light was evaluating the Brilliant Canyon as the site of what would be their lowest and largest dam on the Kootenay River as early as 1934. In a report prepared for the WKP&L Board, Lorne Campbell, General Manager, evaluated future power requirements and how a large dam at Brilliant would help to meet these. He concluded that the huge capital outlay required for its construction could only be justified if storage rights were obtained on Kootenay Lake.As an increase in the water level on Kootenay Lake would flood valuable agricultural land on both sides of the border, progress on such negotiations through the International Joint Commission was slow. WKP&L decided to push ahead with a new dam located downstream of the originally-proposed Granite Dam which was to be sited just upstream of the Taghum railway bridge, and which had been vehemently opposed. Corra Linn was built during the Depression with the expectation of eventually accommodating the extra Kootenay Lake storage once agreement was reached through the IJC. To further increase existing generating capability during this period, a new and more efficient powerhouse was added to the oldest plant now in service, the No. 2 Plant at Upper Bonnington Falls. Nevertheless, further expansion was on the horizon and design engineering proceeded for the new plant at Brilliant.

The storage rights for Kootenay Lake were obtained on Nov.11 1938, after several disastrous flood seasons persuaded American farmers that they would be better off with elevated lake levels because coupled with the water storage was a commitment from WKP&L to significantly improve drainage out of the lake. This was achieved by additional widening and deepening of the river channel at Grohman Narrows and a general re-contouring of the channel below them to improve the flow of the river to Corra Linn dam. Such improvements allowed for better performance of all the Kootenay River plants during the low-water period as they allowed a deeper drawdown and the passage of a greater volume of water. These changes were effective measures for flood control also, as they permitted a more rapid release of water out of the lake when this was necessary. An additional two feet of storage was negotiated in 1940.

All the same, Campbell was reluctant to commit his company to the new venture which was initially tagged at $8 million. He was not convinced that the new plant was necessary and that from company perspective it could not be justified, as it would be rendered somewhat redundant after the war was over. The push came from Cominco, which by now had a great deal of control over the pioneering electrical company. In June 1941 S.G.Blaylock, General Manager of the Trail operations, sent proposals based on increased power production to the president of WKP&L as well as to the federal government. The new plant would be justified by the increased production of strategic war materials such as ammonia (for explosives), zinc and magnesium. A further consideration - kept under strict secrecy - was the later development of a heavy water plant at Warfield, which would help in the development of the atomic bomb. To help fund the expensive construction, Blaylock was asking for special treatment by the government which would provide specific tax advantages. An arrangement was finally secured whereby the capital costs relating to construction could be written off on an accelerated depreciation schedule.

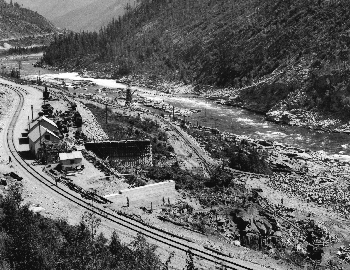

In spite of his reluctance to proceed with outward enthusiasm, Lorne Campbell had commenced with preliminary work in the Brilliant canyon as early as 1940. This work involved the relocation of over 3 km. of railway line to higher ground. The first train negotiated the new track on May 5, 1941. The other major component of preparatory work involved the widening of the river channel below the proposed dam location by blasting out rock obstructions.

|

On April 1, 1942 Kootenay Engineering Company was established as the Cominco subsidiary in charge of the overall project. E.M. Stiles was appointed Chief Engineer and immediately proceeded with his duties. Campbell was retained in a consulting capacity, but he had to turn over two key men who were instrumental to the success of the project: William Tindale and Fred Chapman. Tindale had developed precise engineering plans for the plant and Chapman had been the superintendent of construction on most of the previous plants. Work on the massive project was accelerated immediately.

One of the first tasks was to construct a concrete production plant. This "batch plant" was built alongside the relocated railway so that cement could be delivered directly to it by carload. The aggregate was obtained on the nearby alluvial terrace which was occupied by the orchards and abandoned buildings of the Doukhobor village known as Sion. A screening plant was erected in the summer of 1942 along the provincial highway just to the west of the Verigin Tomb. The gravel deposits were considered clean enough to utilize without washing, although they were high in sand. The field gravel was trucked to the screening and crushing plant, where it was sorted into various sizes that were kept in six 250-ton bins, from which it was released into dump-trucks for transport to the concrete plant, about 1.5 kilometers distant. The batch plant started functioning in September 1942.

Stiles had two major problems to work out. The war-time conditions had put severe demands on strategic supplies such as steel. And with most of the men away in the fighting forces, labour shortages were also a critical consideration. A lot of effort went into securing a special Project Rating from the Americans which would allow the Brilliant dam to get priority status for the procurement of rationed materials and supplies. The labour problem was solved nicely when the resident Doukhobor workers (who were exempt from military service) were persuaded to work on the dam; they eventually provided 60 % of the labour force.

|

|

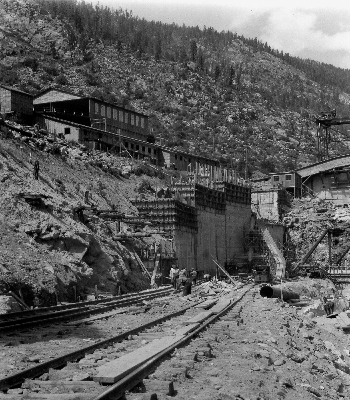

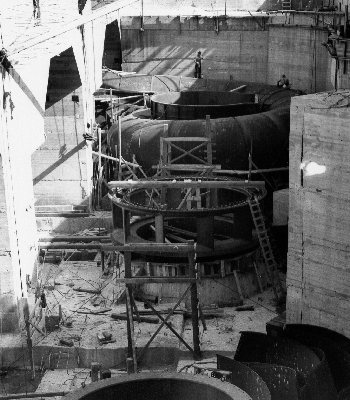

During the winter period the provisional cofferdam was rebuilt to a better standard and work started in excavating the site to the full depth, directly in front of the penstock units. Wooden draft-tube forms were set on concrete bases and steel nose-piers were set in the concrete just downstream of the draft-tube forms, at the point where the draining water was to be split into the paired outlet passages. As the foundations of the power-house rose out of the pit with each new placement of concrete, the intricately-shaped passages which exhaust water from the turbine were formed. These concrete passage-ways would later be precisely mated to steel chambers in which the turbines would run, and the spiral scroll cases would eventually be riveted together from pre-formed sections to feed water from the penstocks to the turbines.

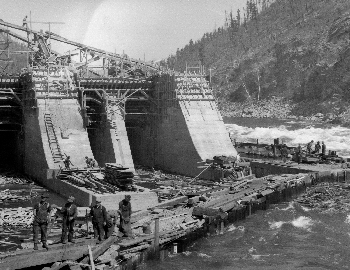

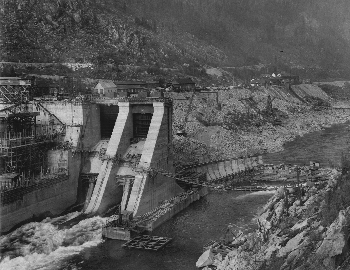

In late winter work also commenced on preparations for the major diversion of the river out of its original bed. There was sufficient room between the cofferdam and the penstock blocks to pour the foundations of the first two spillways. These spillways, however, were atypical: they contained tunnel passages which were large enough to contain the flow of the diverted river. A sluiceway channel was constructed upstream of these passages by selective rock removal and the construction of a concrete deflection wall.

|

|

During the summer of 1943 considerable effort also went into the construction of the immense twin retaining walls which form the right flank of the tailrace channel on the lower level, and - on a higher level - support the bank above the powerhouse access road. The latter retaining wall covered a fascinating piece of history. Prior excavations of this bank revealed a long-hidden timber trestle which had been buried by the original railway line. It was one of the infamous "grasshopper trestles" that were used with such abandon, much to the dismay of William Van Horne, when the original line was being built through here in 1890. Excellent photographs taken of this excavation document three stages in the evolution of the rail line through Brilliant canyon: the earliest trestles, the later filled-in grade which buried the trestles (now being undercut by the excavation), and the recently relocated line 18 feet higher than the original. The summer period also saw major progress on the powerhouse itself. Erection of the steel framing for the powerhouse building commenced in late August. Lower down, work progressed on the turbine-related components.

By November 1943 the dam had been built to full height as far as spillway 2 and cofferdams were being sunk at upstream and downstream locations across the old river channel. These were constructed in modular sections of timber components which were placed in the river channel and sunk by being filled with rock. Once they were firmly settled on the river bottom, a diver would waterproof them by spiking heavy planking against their outer faces, and filling in the irregular holes at the bottom with sandbags or concrete. It was very demanding work. As the flow of water along the old bed was reduced, more of it was forced through the new diversion structure. By late January 1944 the old river bed was being pumped out and prepared for the placement of concrete. The first concrete was poured in the old channel in early March. By May 10 the dam was across the river at full height.

|

|

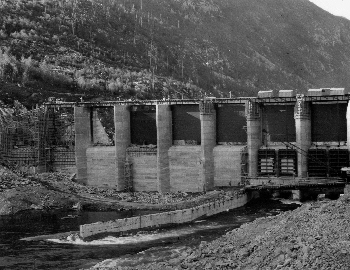

In the fall of 1944 work continued on improvements to the left bank which would facilitate discharge through spillway number 8. A concrete deflector wall was constructed between this spillway and the others, and a considerable amount of rock was removed from the bank just below the last spillway. The rock spoil from these operations was not removed immediately as a decision was made to let the current from the next freshet do the work of clearing it away. This decision proved to be a costly blunder. The freshet which followed washed much of this rock into the tailrace of the new plant. One of the last operations was to seal off the diversion tunnels in spillway blocks 1 and 2.

Neither Campbell nor Blaylock survived long after the new plant started operating. Blaylock, a dedicated workaholic, was feeling the inroads of stress on his weakening heart when he retired to his dream mansion on the West Arm. It failed him completely on November 19, 1945 when he died in Trail Hospital. Campbell's departure, if anything, was even more painful. A broken man, he lived to see his precious company dismantled and sold to Cominco. Always a contentious man, he became even more bitter and isolated, so that when he died in Rossland in the spring of 1947, he had been abandoned by his own family. The legacy of both men endures in the achievements of the corporations which they had nurtured with such dedication, but the price they paid for their success was crushing on a personal level and in the end it overwhelmed them.

Sources:

I am greatly indebted to Corey Sinclair of Fortis BC for allowing me free access to the vast archival resources that document in various ways the operation of West Kootenay Power & Light Company from its inception 110 years ago.

All photographs used are courtesy FortisBC.

All rights reserved. Information is provided for personal use only. Use in any other application without permission is forbidden.