GROWTH OF LOCAL INDUSTRY

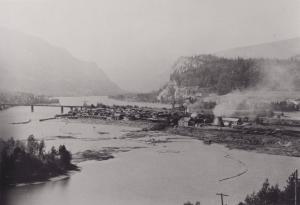

In making cheap transport of logs possible, the Columbia River facilitated

the development of the lumber industry. On this site an impressive sawmill

operated for half a century. Initially known as the Edgewood Lumber Co., the

sawmill was relocated to the abandoned Sproat's Landing site in 1910. William

Waldie and Sons, as the mill was known after 1928, was a major employer in the

growing community. Although bought out by Celgar Development Co. in 1952, the

mill continued operations until 1961.

April 27, 1963. The Makaroff house is bathed by a red glow originating from the fire, directly across the river. The river, impregnated by its glow, seems blood red. The entire family is spell-bound by the huge fire which rages through the whole long and memorable night. Memories of his 27 years of employment flash through John Makaroff's mind as he watches the flames which are destroying fifty years of history. He cannot fight back the tears.

April 30, 1934. Fifteen year old John Makaroff has made up his mind to approach John Waldie about getting a job at the mill. As the eldest son, he is feeling the obligation to support the family of three children and his widowed mother. After explaining his plight he is sent away, greatly disappointed, as he is underage. That evening, there is a knock on the door of the modest Makaroff household. It is John Waldie, coming to see for himself the desperate situation the family is in. He makes up his mind immediately. Young John starts work the next day.

The Great Depression. The Waldies try to keep the mill going at all costs to keep the workers at least partly employed. As everywhere across the nation, the trains bring desperate men looking for work. Although the Waldies can't offer work, they offer food and a warm place to spend the night. One day, the cook refuses to provide food to some dozen vagrant men. When Mr. Waldie hears of it, he storms into the kitchen and immediately fires the cook. Then he proceeds to make sandwiches for the hungry men.

As these vignettes show, the Waldie Mill was far more than the major employer for the growing community of Castlegar. With a genuine belief in their responsibility for their own workers and for the welfare of the broader community, the Waldies in many ways became a social institution in our valley. For nearly half a decade, development in the area was shaped in good measure by the ups and downs of the Waldie Mill and the pace of everyday life was measured by the sound of its mill whistle.

William Waldie Sr. moved his family to Nelson in 1896, to seek his fortune in

the booming mining business. His practical business sense soon paid off, and in

a decade he did well enough to be in position to look for other investments. As

his own father had exposed him to the sawmill business in the family enterprise

on Georgian Bay, Ontario, he decided to pursue his instincts and to invest

heavily in a lumber operation at Edgewood, on the Upper Arrow Lake. He soon

realized that the future growth of the Edgewood Lumber Company was severely

limited by its isolated location, and as he was a major shareholder, he

convinced his partners to seek a better location.

He realized that the abandoned Sproat's Landing site offered the

pefect setting for his mill. It was located at the point where the current

of the Columbia River picks up speed after its leisurely flow through the

Arrow Lakes; also there were strategically placed small islands which

would permit anchorage of boom logs to develop a ponding area. The growing

community across the river would provide both a work force and a local

market. But most important, the C.P.R. had a rail line running right past

the site, and this line could ship his product right across the nation.

|

|

His decision to relocate to Castlegar must have also been influenced by the fact that at the very time he was contemplating the move, the Yale-Columbia sawmill at Westley was lost in a spectacular fire during its eighth year of operation. The loss of the mill which had extensive logging rights along Lower Arrow Lake created a vacuum which could be instantly filled by the relocation of his already viable enterprise.

In 1909 the property was secured, and lumber was cut at the Edgewood Mill for the erection of new buildings at Castlegar. New machinery was ordered and installed and in 1910 the new Edgewood Lumber Company mill commenced operations. The first logs milled at the new site were from the unused log inventory from the burnt-out mill at Westley. These logs were not consumed by the fire as they were still in booms on the lake and thus protected from the flames. Cutting still continued along Upper Arrow Lake, especially in the vicinity of Whatshan Lake; however new timber rights were sought and procured along Lower Arrow Lake and near Castlegar, including the unused cutting rights of the now defunct Yale-Columbia enterprise.

The mill itself evolved over time. Many photographs document this transition from the modest beginnings to the expansive operation of the 1940's. The first decade was difficult: two fires (in 1913 and 1916) destroyed large portions of the mill and were contributing factors in its evolution. The former fire was apparently started by a careless worker who knocked over a kerosene lantern. He was promptly fired, and went on to a presumably safer and more productive venture when he founded the Capozzi winery in Kelowna.

|

|

Transport of logs was chiefly by water: down the Arrow Lakes and Columbia River in the form of large booms. These were towed by powerful tugs of which the "Elco" was the best known. Her name is derived from the initials of the parent company. Booms on the lakes were fed by logs that shot down mountainsides in extensive flumes which channeled them to the booming grounds. The most famous was a flume several miles long which sent logs from Whatshan Lake to the Lower Arrow Lake near Needles; it was built because the Whatshan River was itself too turbulent and produced endless log jams. Where flotation was not feasible, horse drawn transport was used. Mechanization in the field did not play a major role until the 1940's.

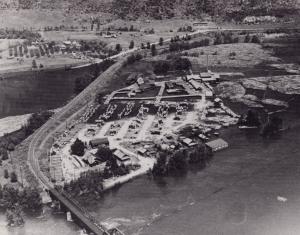

Logs booms were broken up upstream of the railway bridge and the logs were guided by chains of boom logs into the mill pond through a gap in the cribbing between Breakwater Island and the main shore. Once in the pond, the logs were kept captive by other boom logs which were stretched out between Breakwater Island, Waldie Island and the main shore. Appropriate logs were nudged toward the 'jack-ladder', a chain ramp by means of which they were dragged out of the water and onto the sawmill carriage. Here they were milled into boards with vertically oriented double cutting band saws, whose blades had to be sharpened regularly in the filing shop. Rotary blades were used for cross-cutting the lumber into specific lengths. The freshly cut lumber was transported out of the mill on the 'green-chain' where it was manually sorted. The green-chain was located on an extensive elevated deck which connected to all other parts of the mill. Sorted lumber was hauled on wagons which were of two types: some were single axle and had to be drawn by workers; others were dual axle wagons drawn by horses. Lumber was loaded off the wagons and piled into stacks on the ground level. There was quite a drop from the deck to the ground and Betty Price (Lampard), who grew up at the Waldie Sawmill, remembers a wagon and its horse tumbling off. After a suitable drying period, the lumber was transported to the planer mill for final finishing. An ingenious system of wooden rollers was used to feed lumber to the planer mill. The finished product was of three basic types: structural lumber, lath (slats used as a plaster base), and cedar shakes. The entire operation was run by steam which was produced by four boilers located in a building adjacent to the sawmill; the fires were fed by wood waste such as sawdust and mill ends. Poorer waste (bark etc.) was burnt in the large beehive burner which dominated the mill.

In addition to satisfying local markets, the mill sent lumber to distant regions, notably the Prairies. C.P.R. constructed two different spur lines into the mill compound. The earlier version was a long trestle which left the main line just below the present-day Brilliant School. This was replaced later by a spur angling down the embankment as it approaches the railway bridge. The trestle was abandoned as it was expensive to maintain and C.P.R. management had by now satisfied themselves that the bridge could withstand the stresses imposed by trains shunting back and forth as they serviced the new ramp to the mill.

Much of the work force was resident at the mill. Over a dozen small cabins can be seen in the earlier photos; these were available at modest cost and board was also available in the cookhouse. Married employees lived in town or adjoining villages and walked to work. Crossing the railway bridge was especially hazardous and several close calls and one death led to the construction in 1913 of a pedestrian walkway which was attached to the bridge. This remained in use until it was dismantled by the Ministry of Transportation & Highways in spring of 2003. Somewhat later, several houses were constructed between the office building and the repair shop and these were rented to married workers whose occupations were fundamental to smooth running of the mill: the Walners (Elmer was planer mill foreman), Lampards (Bert was a millwright), Houstons (William operated the steam plant), and the MacKinnons. John Waldie also resided at the site. Unless there was exceptional demand, the mill was generally closed for three months each year for maintenance. During the Depression no paying markets could be found. Operations were curtailed and a system of bartering was worked out. Instead of cash, employees were paid promissory notes for value in lumber; these would be accepted as cash by the local merchants and in turn passed on to wholesalers who were in better position to get reimbursed in Waldie lumber. Initially, the working day was 10 hours; later it was reduced to 9 and eventually 8. During the war, demand for lumber gradually picked up and the mill started running a second shift. Wages seem low by today's standard (John Makaroff's starting wage was 25 cents per hour), but there were few deductions and costs were generally low as well. There were other rewards. The company organized picnics to Deer Park on their tugboats and at Christmas, the "Old Man" saw to it that every worker's child received a gift valued at about a dollar. Lumber was sold to employees on extremely generous credit terms if they were in need. The Waldie mill donated all the lumber for the construction of the Castlegar Community Hall and many Waldie workers donated their labour.

For the children that lived at the mill site, the mill offered wonderful opportunities for play and adventure. Betty Price (Lampard) vividly remembers her childhood spent at the mill. During the winter, the trail into the site from the railway bridge became a toboggan run: under the right conditions the children would fly past the office building, then the row of residential housing, past the repair shop - stopping only as they neared the ramp leading onto the platforms (or "trams", as the children called the elevated decks). There was a skating rink near the breakwater, which attracted kids from the whole village. A huge bonfire was built on the bank to provide warmth. But only the resident children had access to the real secret play-places: the warehouse where small chunks of tar could be procured for use as chewing gum; or the dry kiln, whose rock-filled counterweight bins made a great ride up and down every time the massive doors were opened.

The most prosperous times for the mill were in the late 1920's - before the Crash - and in the 1940's. In the early 1920's three of the four Waldie sons (Robert, John, and William Jr.) came of age and joined in mill operations. To better reflect the management of the mill, the name of the enterprise was changed in 1928 to William Waldie and Sons Ltd. William Waldie Sr. died in 1932 and the entire community felt the loss in his passing. The void was soon filled as the boys took over with Bob being office manager, John in charge of mill operations, and Bill looking after the logging. In the 1940's the mill prospered again until it received a serious setback. In 1948 heavy winter snowfalls combined with warm temperatures in late spring to produce a record flood in early June. A good part of the lumber inventory was lost when it either got washed away or the lumber was warped badly as the piles fell over into a tangled mess. Operations soon resumed, however, and the mill entered the fifties.

|

|

In 1952 Canadian Cellanese Corp. acquired the Waldie mill and started with plans for a new sawmill and pulp mill further upstream. The Waldies continued to operate the mill for the new owners and the general community was unaware that a significant change had taken place. In 1958 the Waldie brothers retired and for a few years refocused their attention to the operation of the retail lumber and hardware store now known as Mitchell Supply. On June 21, 1961 the new mill at Westley started operating and the hum and rattle of machinery stopped at the Waldie site forever. Later that year, demolition of the old mill was begun. A decision was made to burn the remaining structures after salvageable materials were recovered. Fire broke out three days prematurely, however, when a spark from a welder's torch set off the inferno in the old dry kiln. The immense blaze lasted long into the night, attracting curiosity seekers from miles around. By the next morning the mill which had become entwined in so many peoples' lives was only a smouldering pile of ashes and rubble. Today the site is occupied by the sewage treatment facility for north Castlegar.

Aside from machinery components which are widely scattered across the site previously occupied by the mill, there are still some intact structures. These can be seen along the Waldie Island Trail which I developed for the Friends of Parks and Trails Society in 1996 to reclaim some of the rich historical heritage along this important portion of the Columbia River. The repair shop foundation is still recognizable ; the tugboats used to tie up just below it. Further along, remnants of the cribbing on Breakwater Island are prolonging the inevitable outcome in their battle with the never-yielding current. In the old mill pond, pilings mark the site of the jack-ladder which fed logs into the jaws of the hungry mill for such a long time. And in places one can still see old boom-sticks which were left stranded on Waldie Island and the forest of the adjacent shoreline by the flood of 1948. The area once overshadowed by the beehive burner where cedar shakes were produced in such vast numbers is now overgrown by a forest of cottonwoods; the trees share the space with red-osier dogwood, willow, wild rose, hawthorn, wild hop, and nightshade. A whole new universe of animal life has again occupied the many environmental niches that gradually reappeared and which collectively add such complexity to this valuable wetland - so recently reclaimed by nature.

All rights reserved. Information is provided for personal use only. Use in any other application without permission is forbidden.